Is surgery really the best option for a patient who experiences a first time shoulder dislocation? A considerable amount of effort has gone into research studies trying to answer this question, but controversy remains. A recent article in this month's issue of Arthroscopy sheds more light on this topic and might help us understand why younger patients could benefit from earlier surgical treatment.

Is surgery really the best option for a patient who experiences a first time shoulder dislocation? A considerable amount of effort has gone into research studies trying to answer this question, but controversy remains. A recent article in this month's issue of Arthroscopy sheds more light on this topic and might help us understand why younger patients could benefit from earlier surgical treatment.

It has long been known that age at the time of first dislocation is the number one predictor of future dislocations. This is one case where younger patients seem to do worse. They are much more likely than adults to experience repeat dislocations in the future. The reason for this has generally been assumed to be related to higher activity levels in younger patients and more participation in contact sports.

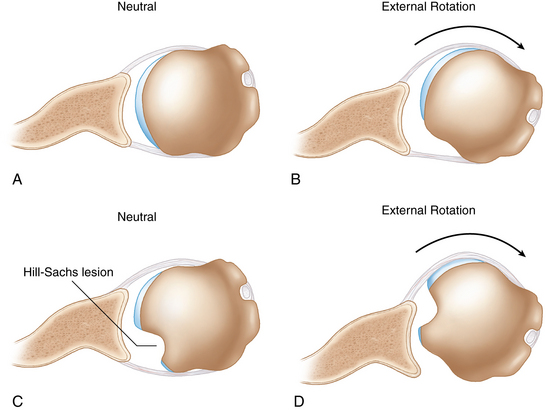

However, this study showed that the actual nature of the injury to the shoulder might be different in younger patients. The study found that adolescents are more likely than adults to have a particularly problematic variety of what orthopedic surgeons call a Hill-Sachs lesion. This is an injury that occurs to the ball or head of the humerus as the shoulder dislocates. When the shoulder dislocates the ball may strike the socket, creating a depression in the humeral head referred to as a Hill-Sachs lesion (see picture). In the current study, adolescents were much more likely than adults to have a Hill-Sachs lesion in a certain location on the head, or one that is large enough, that makes it easier for the shoulder to dislocate again in the future. With each dislocation this defect may only get larger, further increasing future dislocation risk.

The particular nature of the Hill-Sachs lesions seen in adolescents helps explain why we see higher recurrent dislocation rates in this population and supports the argument that earlier surgical intervention may be better in these instances. In fact, a commentary published on this article in the same issue notes that this study makes a "compelling case" for surgical treatment of adolescent first time dislocators.

In my practice, I generally try to be as conservative as possible with surgical treatment options. But, in terms of the adolescent first time shoulder dislocator, it is increasingly looking like the most conservative approach might actually be the surgical one.